It is 26 October, 1960. Democratic Senator John Kennedy and Republican Vice President Richard Nixon are deadlocked in the presidential election. Each candidate is looking for an advantage, while simultaneously trying to avoid any missteps that will either diminish voter turnout, or swing a voter to the rival’s camp. Each candidate is also hoping to avoid an “October Surprise”, and since it is October….

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. took part in a sit in at the segregated Magnolia Dining Room in Rich’s department store on 19 October. He and fifty other protesters were arrested and jailed. All of the other protesters were released within twelve hours, but King was kept in prison. On 25 October he appeared in front of a judge, who informed King that since he had violated probation, he was being sentenced to four months hard labor at Georgia’s Reidsville prison. With a bang of a gavel King is remanded to Reidsville, which is deep in rural Georgia.

Stunned, King remembers that he had been cited for a traffic violation on 4 May, 1960, when he had been pulled over, and the police officer informed him that since he was now living in Georgia he needed to have a Georgia, not an Alabama license. Since his Alabama license hadn’t expired, King hadn’t bothered to get a Georgia license, and since he knew that the police would harass him for any reason they could find, he simply paid the fine and forgot about the matter. What he didn’t know was that his lawyer had agreed that King would be on probation for the offense.

Sending King to Reidsville is the equivalent of lynching him. There is little doubt in the mind of Coretta, his wife, that King will either be “shot while trying to escape”, or killed by an “accident” while serving his four months of hard labor. Coretta, who is pregnant with her third child, reaches out to both the Kennedy and Nixon campaigns for help in freeing her husband from an unjust, and possibly fatal sentence.

Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color line in 1947, and who is currently serving as an advisor to the Nixon campaign, strongly urges Nixon to do whatever he can to free King. At the same time Robinson is making his case, Deputy Attorney General Lawrence E. Walsh (who will serve as special counsel investigating the Iran Contra affair during the Reagan administration) drafts a Justice Department statement urging that King be released. Two copies of the statement are prepared, one for President Eisenhower, and one for candidate Nixon. Eisenhower stays quiet on the matter, but it is Nixon’s silence that is far more powerful, since he is campaigning for the office Eisenhower will vacate in a little over two months.

The Kennedy campaign has a different reaction to Mrs. King’s request for assistance. Harris Wofford, who is advising the Kennedy campaign on civil rights, suggests that Senator Kennedy call Mrs. King to let her know that he is thinking of her and her family. This idea is bumped up to Sargent Shriver, Kennedy’s brother in law, who catches Kennedy just as he’s about to leave Chicago for a swing through the upper Midwest. When Shriver suggests calling Mrs. King, Kennedy first calls Ernest Vandiver, Georgia’s Democratic governor, and asks him to intervene and free King from what is obviously an attempt to murder the civil rights leader. When that call is concluded, Kennedy calls Mrs. King, and he says, “I know this must be very hard for you. I understand you are expecting your third child, and I just wanted you to know that I was thinking about you and Dr. King. If there is anything I can do to help, please let me know.”

Mrs. King is both shocked and consoled by this act of compassion, empathy, and kindness. She tells her friends, who tell others, and soon word of the call is spreading among the Black community. This phone call is followed up by a phone call from Bobby Kennedy, future attorney general, to Governor Vandiver and the judge who had sentenced King to four months of hard labor. Within hours King is released and safely at home.

Martin Luther King, Sr., had publicly stated his support for Nixon a few weeks earlier, purely on religious grounds, since as a Baptist minister he “could never vote for a Catholic.” After his son was released, King switched to Kennedy with this statement:

“Because this man was willing to to wipe the tears from my daughter in law’s eyes, I’ve got a suitcase of votes, and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy and dump them in his lap.”

When Kennedy heard that King Sr. was going to support him, even though he was a Catholic, he quipped, “imagine Martin Luther King. Jr. having a bigot for a father. Well, we all have fathers, don’t we?” Joking aside, Kennedy and his campaign strategists knew that that phone call to Mrs. King was political gold. Over the next two weeks they printed up millions of leaflets for distribution outside of Black churches across the country. The phone call and leaflets paid huge dividends in those states where Blacks were eligible to vote, and Kennedy eked out a victory over Nixon on election day. These figures from Theodore White’s masterful The Making of the President 1960 show just how crucial the Black vote was in Kennedy’s squeaker of a win:

Illinois-27 Electoral College Votes, won by Kennedy with a margin of 9,000. 250,000 Black voters in this state voted for Kennedy.

Michigan-20 Electoral College Votes, won by Kennedy with a margin of 67,000. 250,000 Black voters in this state voted for Kennedy.

What if Nixon had called Mrs. King?

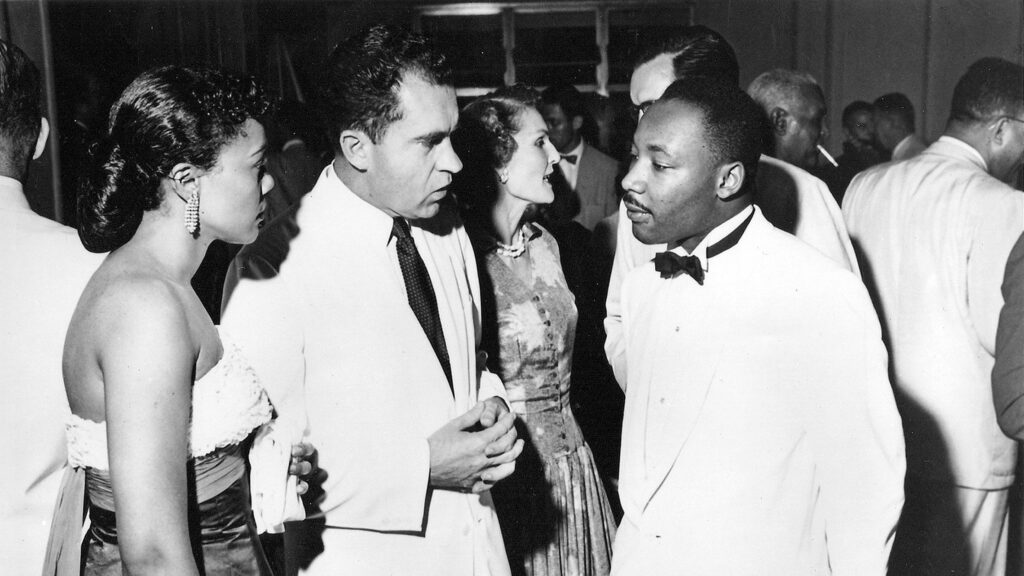

Ironically Nixon had a much closer relationship with King than Kennedy did. The two men met in Ghana in 1957, where they struck up a friendship. Three months after that meeting King came to Nixon’s offices in the Capitol, and after that meeting King wrote Nixon to thank him for his behind the scenes work on the Civil Rights bill that President Eisenhower was trying to get past segregationist Democratic Southern Senators. In his letter King wrote:

….”how deeply grateful all people of goodwill are to you for your assiduous labor and dauntless courage in seeking to make the Civil Rights Bill a reality…this is certainly an expression of your devotion to the highest mandates of the moral law.”

Nixon responded to this letter with this:

“I am sure you know how much I appreciate your generous comments. My only regret is that I have been unable to do more than I have. Progress is understandably slow in this field, but we at least can be sure that we are moving steadily and surely ahead.”

When Nixon gained the Republican presidential nomination in 1960, he, in the words of Thedore White in The Making of the President 1960, “weighed the strategy of the election…considering the alternatives of an advanced civil rights program that could win Negro votes in key Northeastern industrial states as against a program that by moderation could win the votes of Southern Whites and thus carry the states of the Old Confederacy.”

On the day King was sentenced to hard labor, Nixon had some polling data indicating that Texas, Louisiana, and South Carolina were in play. Those three states would net Nixon 42 Electoral College votes. Calling King could have put those states out his reach, along with the state of Georgia, where Nixon held a rally in August that saw over 150,000 people turn out to hear a man from the party that had destroyed the Confederacy a century earlier.

Nixon could have aligned Black voters with the GOP with a single phone call. Instead, he chose to remain silent. Despite pleas from Jackie Robinson that he call Mrs. King, which Nixon dismissed as “simply grandstanding”, Nixon did nothing, letting Kennedy hit a base hit on a 3-2 count, bases loaded situation.

At the end of the day Nixon’s efforts to win the Solid South didn’t amount to very much. Of the eleven former states of the Confederacy, Nixon only carried three (Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida). Maybe a phone call to a woman fearing for the life of her husband could have flipped the states of Illinois, Michigan, and perhaps even New York. Each state was loaded with Black voters who might have gone for Nixon, especially if word got out that he made the call due to Jackie Robinson’s suggestion. A sports hero in the Black community who could get a presidential candidate to call the wife of a civil rights icon in the Black community. Nixon might not only have won the 1960 presidential race. He could have made the Republican Party the home of Black voters for generations to come.