A good friend asked me this question the other day:

Did America’s Entry into World War I Lead to the Rise of Hitler and the Nazis?

I had to think about this for a bit, so the following are my conclusions, based on my existing knowledge and some research prompted by this question.

Why did the United States Enter World War I?

When World War I began in the summer of 1914, President Wilson issued the following statement of neutrality:

The effect of the war upon the United States will depend upon what American citizens say and do. Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality….The people of the United States are drawn from many nations, and chiefly from the nations now at war. It is natural and inevitable that there should be the utmost variety of sympathy and desire among them with regard to the issues and circumstances of the conflict. Some will wish one nation, others another, to succeed in the momentous struggle. It will be easy to excite passion and difficult to allay it….Such divisions amongst us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend….The United States must be neutral in fact, as well as in name…We must be impartial in thought, as well as action.

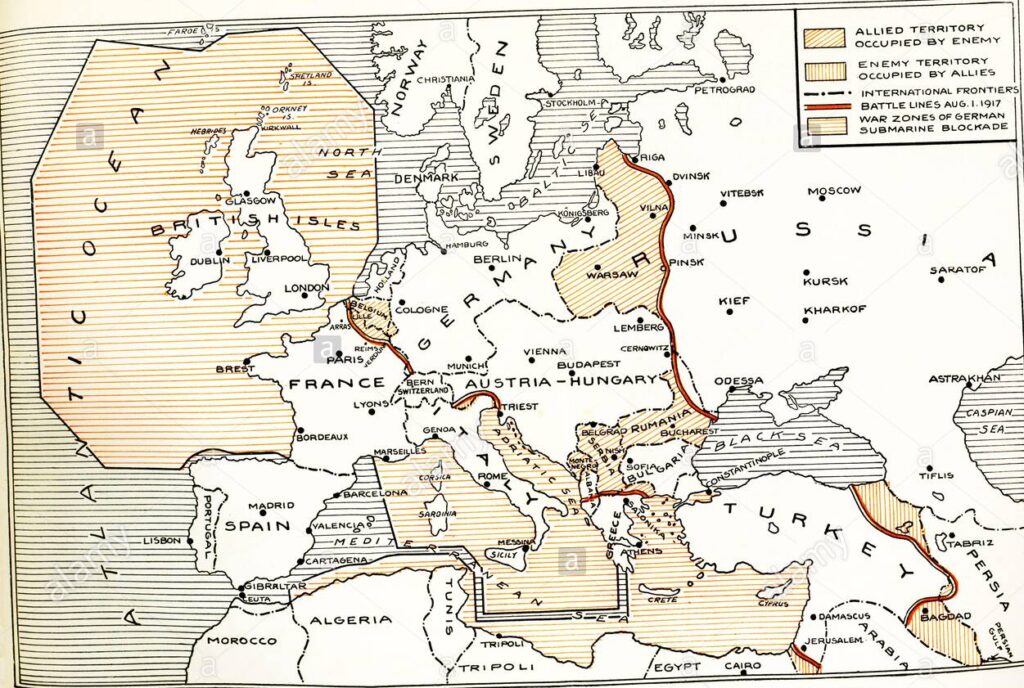

By 1917 the war had become a bloody stalemate. Germany was fighting the British and French in the West, and the Russian Empire in the East. Since the war started in 1914, the German General Staff had been forced to deal with the alliance of France, Russia, and the United Kingdom by concentrating on one front at a time. In 1914 the failure to destroy the French and the British led the Germans to make 1915 a year of holding actions in the West while concentrating on forcing the Russians out of the war. Once the Russians were driven completely out of Poland, 1916 became a year to focus on bleeding the French army to death by attacking the key fortress area of Verdun. By the end of 1916 all Germany had to show for its efforts was that its armies were back where the offensive started, and 500,000 German troops were dead.

As 1917 began the British blockade of the North Sea was being felt by the German citizens as food and fuel supplies became scarcer. By this point of the war Kaiser Wilhelm II was for all practical purposes nothing but a figurehead. The German General Staff was in firm control, making Germany essentially a military dictatorship. It was the German General Staff that insisted that the Kaiser begin unrestricted submarine warfare, meaning that German U-Boats would now be free to sink any ships, even those of neutral countries like the United States, that entered the German declared war zone around the British isles and the northern French coast.

On 31 January, 1917, the German government declared that its U-Boats would begin unrestricted warfare effective immediately, and all ships entering the war zone were fair targets. This was a dangerous gamble, since it risked bringing the United States into the war on the side of the Allies, but the German General staff calculated that the benefits outweighed the risks. The German blockade of Russia was putting enormous pressure on the Russian economy, and that pressure would soon erupt into food riots and the overthrow of the Tsar. A combination of unrestricted warfare against the British, combined with the blockade against Russia, could lead to two of the three major Allied powers dropping out of the war.

When unrestricted submarine warfare began, the outcome exceeded the predictions of the war planners. In February 540,000 tons of shipping bound for the United Kingdom were destroyed; in March, 578,000 tons; and in April, with longer daylight hours thanks to the vernal equinox, 874,000 tons went to the bottom of the Atlantic. The United Kingdom was reduced to a six week reserve of food, and Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, First Sea Lord, warned Prime Minister David Lloyd-George, that if the situation didn’t change soon, a negotiated settlement with Germany might be the only way out of an increasingly desperate situation.

In response to the unrestricted submarine warfare declaration, President Wilson broke diplomatic relations with Germany on 2 February, 1917, but he didn’t yet feel the need for war, despite the sharp turn in American public opinion against Germany. Germany’s increasing disregard for the norms of warfare, whether it was the use of poison gas, the execution of British nurse Edith Cavell for assisting British soldiers escaping German-occupied Belgium, its brutal occupation of Belgium, and now the use of its U-Boats against neutral ships, had turned a majority of Americans against Germany. Public opinion polls also noted a growing sense of national pride, which was manifested in the belief that because America had remained neutral, it had a superior moral position as the “only great nation devoted to the principles of freedom and democracy.”

Yet, Wilson hesitated when it came to asking for a declaration of war. He had very narrowly won re-election in 1916 on a very simple campaign platform: “He kept us out of war”. Wilson also had a personal aversion to war and combat. He had been born in 1858 in Staunton, Virginia, and as an adult he wrote: “My earliest memory is of being 3 years old and playing in our yard and hearing a passerby announce with disgust that Abraham Lincoln had been elected president and soon there would be a war.” Wilson’s father was a Presbyterian minister, and the family moved throughout the South during Wilson’s childhood. Wilson was seven years old and living in Georgia when the Confederacy surrendered, so he had vivid memories of what war does to a society. Three events convinced him to ask for a declaration of war in April of 1917:

Destruction of American Ships-Between 31 January, 1917, when Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare, and 2 April, when Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress to ask for a declaration of war against Germany, ten American merchant ships had been destroyed by U-Boat attacks, with a loss of 24 American lives.

The Zimmerman Telegram– On 1 February, 1917, Arthur Zimmerman, German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, sent a coded dispatch to the Germany’s Ambassador to Mexico, which stated:

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain, and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

British cryptoanalysts intercepted and decoded the telegram, and the full text was provided to the American Embassy in London, which forwarded it to Washington, where it was read by President Wilson. At first the telegram was greeted with skepticism by the American public, but on 29 March Zimmerman gave a speech in the Reichstag, stating that the telegram was genuine, and that he hoped the Americans understood that Germany would not fund Mexico’s war with the United States unless the United States declared war on Germany.

The Russian Revolution-Wilson was probably the most self-righteous, holier than thou president ever elected, until Jimmy Carter arrived in the Oval Office in 1977. Going to war over ship sinkings, or the ludicrous threat of Mexico allying itself with Germany in order to regain the territories it lost in 1848, wasn’t very noble. Going to war to make “the world safe for democracy” gave the endeavor the ring of a righteous crusade, but Wilson couldn’t claim that the United States was on the side of democracy when Russia, one of the three major Allied powers, was an absolute monarchy. That changed on 15 March, when Tsar Nicholas II, bowing to a growing rebellion that was sparked by a food riot in the capital city of Petrograd, abdicated the throne and turned power over to a provisional republican government. Now Wilson had the moral crusade he wanted, and it was this crusade that framed his message to Congress on 2 April, 1917:

We have no quarrel with the German people. We have no feeling towards them but one of sympathy and friendship. It was not upon their impulse that their Government acted in entering this war. It was not with their previous knowledge or approval. It was a war determined upon as wars used to be determined upon in the old, unhappy days when peoples were nowhere consulted by their rulers and wars were provoked and waged in the interest of dynasties or of little groups of ambitious men who were accustomed to use their fellow men as pawns and tools. Self-governed nations do not fill their neighbour states with spies or set the course of intrigue to bring about some critical posture of affairs which will give them an opportunity to strike and make conquest…..

A steadfast concert for peace can never be maintained except by a partnership of democratic nations. No autocratic government could be trusted to keep faith within it or observe its covenants. It must be a league of honour, a partnership of opinion. Intrigue would eat its vitals away; the plottings of inner circles who could plan what they would and render account to no one would be a corruption seated at its very heart. Only free peoples can hold their purpose and their honor steady to a common end and prefer the interests of mankind to any narrow interest of their own.

Does not every American feel that assurance has been added to our hope for the future peace of the world by the wonderful and heartening things that have been happening within the last few weeks in Russia? Russia was known by those who knew it best to have been always in fact democratic at heart, in all the vital habits of her thought, in all the intimate relationships of her people that spoke their natural instinct, their habitual attitude towards life. The autocracy that crowned the summit of her political structure, long as it had stood and terrible as was the reality of its power, was not in fact Russian in origin, character, or purpose; and now it has been shaken off and the great, generous Russian people have been added in all their naive majesty and might to the forces that are fighting for freedom in the world, for justice, and for peace. Here is a fit partner for a league of honour.

It is a distressing and oppressive duty, gentlemen of the Congress, which I have performed in thus addressing you. There are, it may be, many months of fiery trial and sacrifice ahead of us. It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts — for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free. To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.

When I read Wilson’s speech to Congress, with its clarion call for democracy and freedom, I burst into laughter. Here was a man who was asking the nation to go to war to make the world safe for democracy, while at the same time he was leading a vigorous campaign to deny women the right to vote. Wilson was also an ardent White supremacist, who said this when meeting with members of the National Association for Equal Rights, after he imposed rigid segregation on the federal workforce:

Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen. If your organization goes out and tells the colored people of the country that it is a humiliation, they will so regard it, but if you do not tell them so, and regard it rather as a benefit, the will regard it the same. The only harm that will come will be if you cause them to think it is a humiliation…If this organization is ever to have another hearing before me it must have another spokesman. Your manner offends me.

His hypocrisy and priggish self righteousness notwithstanding, Wilson got Congress to vote for war with Germany on 6 April, 1917.

Germany’s Response to the American Declaration of War

It would be months before the first American troops arrived in France, and this was the critical time for Germany to do everything it could to win the war, or to make enough gains on the battlefield so that peace talks could commence. After the American declaration of war, Germany secretly transported Russian Communist leader Vladimir Lenin from Switzerland to Russia, where he undermined the new provisional government, which he ultimately overthrew on 7 November, ushering in the world’s first Communist government. Within two months of overthrowing the provisional government, Lenin had signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, taking Russia out of the war and yielding vast swaths of territory to Germany.

Despite its success in knocking Russia out of the war, Germany had an abysmal intelligence failure when it came to exploiting a serious issue in the French army. When word of America’s entry into the war reached French soldiers at the front, a tremendous burst of euphoria erupted. More than 1 million French soldiers had been killed since the start of the war, and America’s entry into the war gave every poilu on the front lines that most sought after emotion: hope. That hope and euphoria was buoyed even more by the announcement of the upcoming offensive against the German occupied positions at Chemin des Dames. General Nivelle, who was leading the offensive, promised that this drive would end the war, since he would be perfecting a tactic he had already used successfully during the Verdun campaign: a creeping artillery barrage timed to advance just ahead of the infantry divisions.

Nivelle launched his offensive on 16 April, ten days after America declared war on Germany. The operation was a disaster, and the fragile psychology of the French soldiers snapped. On 3 May the French 2nd Division refused orders to attack, and that mutiny soon metastasized throughout the French army. By 28 May mutinies had erupted in 13 divisions, and a record 27,000 French soldiers deserted. German intelligence never knew of this mass mutiny. If Germany had known about this unprecedented disruption, it could have easily broken through at numerous points along the line, and perhaps conquered France before the first American soldier set foot on the European continent.

The Ultimate Effect of American Troops on the War Effort

In March of 1918, with Russia now completely out of the war, and American forces not yet fully in place, Germany launched Operation Michael along the Western Front. Using new tactics, along with the most devastating artillery barrage to date, German forces broke through and advanced in a steady stream against British and French forces, pushing the Anglo-French back to the Marne River. As more and more American forces arrived in France, the French and British were able to blunt the German offensive, and launch one of their own on 8 August. When that combined Allied offensive began, it never stopped. On 3 November, 1918, German sailors at Kiel refuse orders to get their ships underway as part of mass attack against the Royal Navy dreadnoughts and cruisers blockading the North Sea. By the end of the day sailors had control of nearly every German warship at anchor. This mutiny was the beginning of the German Revolution, which ultimately forced Kaiser Wilhelm II to flee to the Netherlands on 9 November. With the Kaiser gone, a provisional republic was quickly formed. It was this provisional government that faced the reality that the Allied offensive could continue with an invasion of Germany. That stark reality forced the only alternative: asking the Allies for an armistice so that peace talks could commence.

The armistice was not a surrender. While Germany was clearly in dire straits on 11 November, 1918, it was not invaded and conquered. A cessation of hostilities would allow the new government to consolidate power, address the pressing needs of supplying food and fuel to the civilian population, and above all, begin a true democracy in Germany.

The United States had joined the war, and thanks to Germany’s inability to exploit the French mutiny in 1917, combined with a unified Allied offensive strategy, compelled Germany to quit and sue for peace. Entering the war had profound consequences on American and world history, but it was America’s actions after the war that drastically altered the course of human events.

Postwar American Actions/Inactions that Led to the Nazis

Going to war against Germany was relatively easy. The United States spun up its tremendous industrial capability, instituted a draft, and prevailed in numerous battles against the German Army. The hard part came after the fighting ceased. In his request for a declaration of war, President Wilson said that “the world must be made safe for democracy.” On 8 January, 1918, he addressed another joint session of Congress, in which he laid out his goals for a post war society. The speech contained fourteen items which Wilson deemed necessary for a world free of war and conquest in the future. When Georges Clemenceau, Prime Minister of France, read the Fourteen Points speech, he sneeringly said:

“Fourteen Points? The Good Lord only gave us Ten, and do we abide by those?”

It was in the post war environment that Wilson made two fatal mistakes. His first mistake was to bask too much in the enormous exaltation and good will that greeted him when he arrived in France. People treated him as a savior, the man who would end war forever with his Fourteen Points and his idea of a League of Nations, where member states would settle their disputes without going to war. Wilson’s self righteous nature, combined with the wild adulation he received from the Europeans, blinded him to the political reality that the Republicans had gained control of the Senate in the 1918 midterm elections, and any treaty would have to get past Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Henry Cabot Lodge, who truly despised Wilson. Wilson didn’t invite any Republicans to accompany him to the Versailles Peace Conference, so when he returned home with the treaty and the League of Nations Agreement, Senator Lodge had a clerk read the entire treaty into the record before he would even begin hearings on its merits. When the Nobel Prize committed awarded Wilson the Peace Prize in 1919, he foolishly felt that this would vindicate his push for the League of Nations, and get it ratified in the Senate. As a future president could have told Wilson, a Nobel Peace prize doesn’t mean dick to your political adversaries.

The more ominous mistake Wilson made after the guns ceased firing was not ensuring that the nascent German democracy actually took root. Wilson, like many American leaders and politicians, naively assumed that democracy was the default human condition. It’s not, and as one writer so aptly put it, “a democracy in a backward or unstable country simply gets smashed by the best organized power gang.” Germany wasn’t a backward country, but it was most certainly an unstable one. I’m always amazed that Wilson, a man with PhD in government history (to date he is the only president with a PhD) was stupid enough to assume that a country could go from an absolute monarchy to a representative democracy overnight. This naivete is even more astonishing given the history of the Allied powers. Of the four nations drawing up the Treaty of Versailles, only the United States had started out as a representative republic. The following synopsis is illustrative of just how fragile and rare democracy is:

France: The French overthrew their absolute monarchy in 1789, and it went through ten years of turmoil before Napoleon imposed order as a military dictator in 1799. He was absolute ruler of France until 1815, when he was defeated and the previous monarchy was restored. That monarchy was overthrown in 1830, and a new monarchy that was supposedly limited took its place, until it was overthrown in 1848, and the Second French Republic was established. That republic lasted two years until Louis Napoleon, its president, assumed absolute power and named himself Emperor, creating the Second French Empire. Louis Napoleon, aka Napoleon III, was captured at the Battle of Sedan during the Franco-Prussian War, and the Third Republic arose from the ashes of the Second French Empire. By 1918 France had been a stable republic for only 47 years.

Italy: This country became a unified nation-state in 1870 with the absorption of the Papal states and the withdrawal of the French forces that had permitted the Vatican to maintain control of this belt of land that had divided Italy since the 800s. It was a constitutional monarchy until 1922, when Benito Mussolini seized power and transformed the country into a fascist dictatorship. Total lifespan of Italian democracy: 52 years

United Kingdom: This country began as an absolute monarchy. The English Civil War and the subsequent execution of King Charles I ushered in a dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell, which lasted for eleven years until his death and the restoration of the monarchy under King Charles II, son of the executed Charles I. When Charles II died without a legitimate heir, the throne passed to his brother James, who was intent on ruling as an absolute monarch. James was overthrown and replaced as monarch by his daughter and son in law. The head of state remained stable after James was dispatched, but the House of Commons, the only portion of the British government that was directly elected by the people, could be overruled by the un-elected House of Lords, or have its bills vetoed by the monarch, with no ability to override. A significant number of Commons members were “elected” from districts that didn’t have anyone living in them. Others were the brothers of members of the House of Lords, making them puppets of the nobility. Members of Parliament didn’t get a salary, making it impossible for anyone without an independent income to run for office. It wasn’t until the passage of the 1911 Parliamentary Reform Bill that the House of Commons truly became the representative house of the voters. The 1911 reform bill stripped the House of Lords of its ability to indefinitely delay the passage of bills, and it also provided members of the House of Commons with a salary, enabling working class men to run for office. This happened seven years before the United Kingdom joined the United States in Versailles as part of Wilson’s “partnership of democratic nations.”

Wilson tried to keep vengeance away from the Versailles negotiations, but France and Belgium were determined to make Germany pay for the death and destruction inflicted on their countries. After much bitter negotiation the sum of $31 billion ($442 billion in 2021) was reached. Germany was to pay these reparations to in a combination of currency and raw materials. These reparations put enormous economic strain on the new German government, and it was less than a year after Germany was compelled to sign the Treaty of Versailles that the first of several events rocked the foundations of the brand new republic.

On 13 March a group of industrial magnates and monarchists tried to overthrow the government, forcing members of the ruling coalition to flee Berlin. The Social Democratic members of the government called for a general strike to disrupt the coup attempt, which fizzled after a few days.

Shortly after the coup failure, left wing workers in the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland, began a rebellion to show their disgust that the new republic could be so easily threatened by monarchists and fellow right wingers. The government was forced to use the army, which was restricted to 100,000 members under the Versailles Treaty, and elements of right wing militias to suppress the rebellion. Nearly 1,000 workers were killed by the army and right wing paramilitary groups.

On 11 January, 1923, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr Valley. The occupation was a result of Germany defaulting on its reparations payments. Germany had become unable to pay the reparations due to the instability of its currency and its loss of overseas markets. France and Belgium pressed the United Kingdom to join them in occupying the Ruhr, but the British argued for a reduction in the payments and a re-negotiation of the reparations schedule. French President Poincare ordered French troops to occupy the Ruhr and to take coal, steel, timber, and any other materials that could be used in lieu of cash for reparations. Poincare argued that the reparations were not the sole reason for the occupation; rather, the occupation was necessary because Germany was defying the Versailles Treaty. If the reparations were not paid, Poincare stated that the Germans would soon defy other portions of the treaty, thus plunging the world into another world war.

The occupation roiled the already restive German political waters. Workers in the Ruhr instituted a policy of passive resistance, refusing to work. This lack of work worsened Germany’s already fragile economic state, leading to rampant inflation. More ominously the government’s inability to counter the occupation gave further fuel to the right wing elements that despised democracy. One of those right wing elements was a newly formed political party known as the National Socialist German Workers Party, or Nazis for short. Its leader, a World War veteran named Adolf Hitler, was disgusted by the inaction of the government to the occupation, and he expressed his disgust with an attempted coup on 8 November, 1923. The coup failed, but the government’s response to the coup was a far greater failure. Hitler was sentenced to 5 years in prison, but he only served one year before being released. Ten years later he was absolute dictator of Germany.

The moral and political power of the United States came into play only once after the guns of the Great War fell silent and the US Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles. As the Ruhr occupation crisis intensified, Charles Dawes, US representative on the Allied Reparations Commission, came up with a plan to end the occupation by restructuring the reparation payment schedule, reorganizing the Reichsbank under Allied supervision, and loaning Germany $200 million through Wall Street bond issues. These steps ended the occupation, allowed Germany’s industries to revive, and it netted Dawes the 1925 Nobel Peace Prize. This plan showed what America should have been doing once the war ended.

The Dawes plan and the evacuation of French and Belgian troops from the Ruhr, the adoption of a new and stable currency, and loans, especially from the United States, helped Germany to have a remarkable economic recovery. As Germany’s economy recovered and thrived, extremist groups on the right and left lost members and appeal. Then the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression hit. This passage from Palmer’s A History of the Modern World vividly illustrates how a democracy in fragile land can be so easily destroyed:

No country suffered more than Germany from the worldwide economic collapse. Foreign loans abruptly ceased. Factories ground to a halt. There were 6 million unemployed. The middle class had not really recovered from the great inflation of 1923; struck again, after so brief a respite, they lost all faith in the economic system and its future. The Communist vote steadily mounted; large numbers of the middling masses, who saw in communism their own death warrant, looked about desperately for someone to save them from Bolshevism. The Depression also stirred up the universal German loathing for the Treaty of Versailles. Many Germans, still mourning the huge loss of life in the World War, explained the ruin of Germany by the postwar treatment it had received from the Allies–the constriction of its frontiers; the loss of its colonies, markets, shipping, and foreign investments; the colossal demand for reparations; the occupation of the Ruhr; the inflation; and much else.

Any people in such a trap would have been bewildered, resentful, and even receptive to demagogues. But many Germans responded to their crisis with ideas and actions that may have reflected or grown out of Germany’s political experience and position in Europe over the previous three or four centuries. Democracy–the agreement to obtain and accept majority verdicts, to discuss and compromise, to adjust conflicting interests without wholly satisfying or wholly crushing either side–was hard enough to maintain in any country in a crisis. In Germany democracy was itself an innovation, which had yet to prove its value, which could easily be called un-German, an artificial or imported doctrine, a foreign system foisted upon Germany by the victors in the late war.

Conclusion

The entry of the United States into World War I altered the course of the war, but it was the inaction and isolation of the United States after the war ended that provided a significant contribution to the rise of the Nazis. Fortunately the country learned a painful lesson from the mistake it made. When Nazi Germany surrendered in May of 1945, a plan was in place for the United States to reconstruct and rehabilitate the shattered nation into a genuine democracy. The Office of Military Government , United States (OMGUS) took direct control of Germany for four years until genuine elections could be held, and a new Federal Republic of Germany arose from the ashes of the Third Reich. Germany’s democracy has endured for the last 72 years, and it was strong enough to withstand the absorption of the Communist German Democratic Republic in 1990.

The lesson of World War I for the United States is not isolation after a war, but engagement to secure the peace. Another lesson is to factor in the cost of the war’s aftermath along with the cost of the war itself. Or, as my high school baseball coach said when one of my teammates was about to become a dad at the tender age of 17:

If you can’t afford a condom, you can’t afford a baby.