When Glen Youngkin, a venture capitalist who had never run for office, became the Republican nominee for the governor of Virginia, he latched onto a popular conservative talking point: critical race theory. I don’t know what critical race theory is, but it seems to scare the living Hell out of American conservatives to the point that they are examining historical curricula with the precision used by parents to comb lice nits out of their children’s hair. In any event Younkin and the Virginia Republicans rode the fear of teaching critical race theory to victory in last November’s elections, sweeping the Democrats from power in the governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general races, along with capturing the control of the Virginia House of Delegates.

One of the newly elected Republican delegates is a gentleman named Wren Williams, who is now in the news, albeit not for good reasons. Mr. Williams is the author and sponsor of House Bill NO. 781, which is designed to ban “divisive concepts” from being taught in Virginia public schools. Section B3 of Mr. William’s bill states:

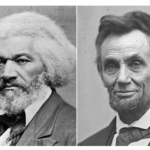

The founding documents of the United States, including the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, the Federalist Papers, including Essays 10 and 51, excerpts from Alexis do Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, the first debate between Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, and the writings of the Founding Fathers of the United States.

I live in Maryland and work in Virginia, and I don’t have children, so unless Virginia changes laws on speed limits or the amount of tax charged for beer purchases (full disclosure: I do all our beer shopping at Total Wine in McLean because Virginia’s alcohol taxes are lower than Maryland’s), I don’t pay any attention to bills winding their way through Virginia’s legislature. I wouldn’t have known about Mr. Williams’ bill, but the Washington Post’s outstanding Retropolis column, which covers national and local items of historical interest, wrote a great piece about it on 14 Jan 2022. You can read the column here.

After reading the column and Mr. Williams’ proposed bill, I was very glad that I don’t have children, and even happier that if I had a child he wouldn’t be a student in a Virginia public school. It’s doubtful that Mr. Williams will read this post, but the history nerd in me couldn’t let his ignorance go unpunished.

What Were the Lincoln-Douglas Debates?

The debates were between Republican Abraham Lincoln and Democrat Stephen Douglas. Douglas was running for re-election as one of Illinois’ two U.S. Senators. Lincoln, who had served one term in Congress as a member of the Whig party, was seeking to replace Douglas in the Senate. After both men gave speeches within a day of each other in Springfield and Chicago, they decided to have a debate in each of Illinois’ seven congressional districts. The debate format, which would make today’s presidential candidates cry like a little child, mandated that one candidate would speak for an hour. The opponent then had 90 minutes to rebut, followed by the first candidate having 30 minutes to respond. The topic of all seven debates was the same: the spread of slavery into the territories conquered by the United States from Mexico in the Mexican-American War of 1847-48.

Since Senators were chosen by state legislatures in 1858, both men hoped that their performance in the debates would inspire enough voters to help their respective party win control of the state legislature in the November election. If the Democrats maintained control, Douglas would keep his seat. If the Republicans gained control, Lincoln would become a U.S. Senator, representing a party that was determined to halt the spread of slavery into the new territories.

Who Was Stephen Douglas?

Douglas was a national figure when the debates began. He had sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1852 and 1856. He had been a member of the Senate since 1847, and he was one of the architects of the Great Compromise of 1850. This compromise was the first attempt to deal with the question of slavery spreading into the new territories. Under the deal which Douglas helped broker, California entered the Union as a free state, but the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, which allowed a slave owner to pursue and capture an escaped slave into any area of the United States, regardless of whether slavery was banned in that area. Douglas and the other midwives of the Compromise of 1850 hoped that this would settle the matter of slavery once and for all, but their hopes were dashed when the Kansas territory petitioned for statehood.

Under the terms of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, slavery was forbidden in all territory north of 36’30” north latitude, which is the southern border of the state of Missouri. Since slavery existed in Missouri when it petitioned to enter the Union, the compromise was that Missouri could enter as a slave state, and Maine, which entered the Union at the same time, would come in as a free state, thus maintaining the crucial balance of power in the Senate. The Kansas territory lay north of 36’30”.

Douglas stepped into the fray with an idea. Let the people of any territory decide if they want to be a slave or free state, or as he called it “popular sovereignty” (see states rights in the 1950s-1960s). His idea became the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which passed Congress in 1854, and which consigned the Missouri Compromise to the ash heap of history. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act led to a large number of Democrats from the North to abandon the national Democratic party and form the new Republican party, which had one principal tenet: slavery will not spread beyond its current boundaries. Like the Cold War policy of containment of Communism to those nations that were already Communist, the new Republican party was set on containing slavery to the fifteen states and the District of Columbia, where it already existed.

Who was Frederick Douglass?

As you can see from the above header, Frederick Douglass, unlike Stephen Douglas, spelled his last name with two Ss. Frederick Douglass also had one other difference from Stephen Douglas: he was Black. He was born a slave on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in either 1817 or 1818, and there is a very real probability that his master was also his father. Disguised as a merchant seaman, Douglass escaped to freedom in 1838, and he ultimately settled in Massachusetts, where he became a prominent abolitionist. In 1845 he wrote The Narrative Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. The book became an immediate best seller, and it was translated into French and Dutch for publication in Europe, where it also became a best seller.

In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Dred Scott, a slave who was suing his master for his freedom after his master took him into federal territory where slavery was forbidden, didn’t have any standing to sue anyone, since slaves were property and not citizens. Under that ruling Frederick Douglass couldn’t even vote, let alone seek office, so it would have been rather ludicrous for him to debate Lincoln for a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Did Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln Ever Meet?

Yes, they did. When the Civil War began, Douglass ardently campaigned for the Union Army to enlist and train Black men as soldiers. After the enactment of the Emancipation Proclamation on 1 January, 1863, Douglass was invited to the Executive Mansion (it wasn’t officially called the White House until President Theodore Roosevelt had the words White House engraved on stationary in 1901) in the summer of 1863 to discuss the treatment of Black soldiers in the Army and plans to move freed slaves out of the South.

Like nearly all relationships between activists and politicians (see Martin Luther King, Jr. and Lyndon Johnson; Cornell West and Barack Obama), the relationship between Douglass and Lincoln was rocky. Douglass was well aware of Lincoln’s remarks during his first debate with Stephen Douglas, where Lincoln said:

“When Southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery than we, I acknowledge the fact. When it is said that the institution exists, and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying. I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself. If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia,-to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days. What then? Free them all, and keep them among us as underlings? Is it quite certain that this betters their condition? I think I would not hold one in slavery at any rate; yet the point is not clear enough to me to denounce people upon. What next? Free them, and make them politically and socially our equals? My own feelings will not admit of this; and if mine would, we well know that those of the great mass of white people will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment, is not the sole question, if, indeed, it is any part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, cannot be safely disregarded. We cannot, then, make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the South.

Lincoln’s feelings about the “impossibility” of making the newly freed slaves the equals of White men were probably the foundation of his opposition to voting rights for freed Black men, and it was that opposition that led Douglass to throw his support behind John C. Fremont, the presidential candidate of the Radical Democratic Party. Fremont had been the first presidential candidate of the new Republican party in the 1856 general election, but by 1864 he wanted immediate abolition of slavery in the whole country, not just the states in the Confederacy, so he ran as a third party candidate in that year’s presidential election.

On the tenth anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination Douglass was the keynote speaker at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C.’s Lincoln Park. In the decade that had passed since Lincoln’s murder, President Johnson’s impeachment, and the failure of Reconstruction to grant the newly freed slaves true equality, Douglass’ remarks were tempered with criticism and praise of Lincoln. He called Lincoln “the White man’s president”, criticized Lincoln’s tardiness when it came to embracing the cause of emancipation, and called Lincoln out for for his opposition to the expansion of slavery into the new territories while simultaneously vowing to keep slavery intact where it existed. But Douglass also praised Lincoln when he said:

“Can any colored man, or any White man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see of Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word? Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his White fellow countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery.”

tw